Can I Look at Reniassance Art Not as Pornographic

Is the Renaissance nude religious or erotic?

(Image credit:

National Galleries of Scotland

)

A new exhibition explores how the naked form revolutionised painting and sculpture. Cath Pound looks at shifting attitudes and what they reveal nearly society and sexuality.

R

Renaissance artists transformed the class of Western art history by making the nude key to artistic practice. The revival of interest in classical antiquity and a new focus on the role of the epitome in Christian worship encouraged artists to draw from life, resulting in the development of newly vibrant representations of the homo trunk.

The ability to correspond the naked body would become the standard for measuring artistic genius but its portrayal was not without controversy, particularly in religious art. Although many artists argued that athletic, finely proportioned bodies communicated virtue, others feared their potential to incite animalism, often with good reason.

More similar this:

- A Victorian painter of gender fluidity

- How black women were whitewashed by art

- Eight odd details hidden in masterpieces

The Renaissance Nude at the Royal Academy in London explores the development of the nude beyond Europe in its religious, classical and secular forms – revealing not merely how information technology reached its dominant position, but also the often surprising attitudes to nudity and sexuality that existed at the time.

Dosso Dossi, Apologue of Fortune, c. 1530 (Credit: The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

Nudity had appeared regularly in Christian art throughout the 13th and 14th Centuries. As Jill Burke, co-editor of the exhibition catalogue, says: "The get-go figure that is nude repeatedly is the figure of Christ." But from the 14th Century, there was a major shift in people's attitudes to Christian art and the style it could be used in private devotion and worship. "They were interested in the idea of empathy and using images as a way of really feeling the pain of Christ and the saints," says Burke.

As a issue, artists strove to brand images more truthful, with the effigy of Christ, the Saints and other religious figures gradually becoming more tangible. This development is evident in the figures of Adam and Eve, painted by Jan van Eyck for his masterful Ghent altarpiece (completed 1432). Thought to exist amid the first drawn from life, they are astonishingly rich in observed particular. Adam is shown to accept sunburned hands while the linea nigra running over Eve's gently protruding abdomen conspicuously reveals her to be significant.

Jan van Eyck'southward Ghent altarpiece (Credit: Alamy)

In their portrayals of the nude, Van Eyck and other northern artists were drawing on a rich, circuitous native tradition that incorporated not only religious art but also secular themes, including bathing and brothel scenes, produced in media ranging from manuscripts to ivory reliefs. Their development of the rich, lustrous oil painting technique would allow for a far greater level of naturalism.

Naked middle

Northern artists too benefitted from a generally relaxed mental attitude to nudity. "There's a lot of nakedness in things similar pageants in the Due north," says Burke. This was in marked contrast to Italy, where "they had really prescriptive ideas most seeing women's bodies, even in marriage. The husband shouldn't see his wife naked for example," says Burke.

Italians also believed the female body was fundamentally inferior, as co-ordinate to Aristotle they were not formed properly in the womb, defective the heat to push button out genitalia. Although Italian patrons enthusiastically collected Northern female person nudes, perhaps unsurprisingly nearly 15th-Century Italian artists chose to focus on the male person body, although there were notable exceptions such as Botticelli.

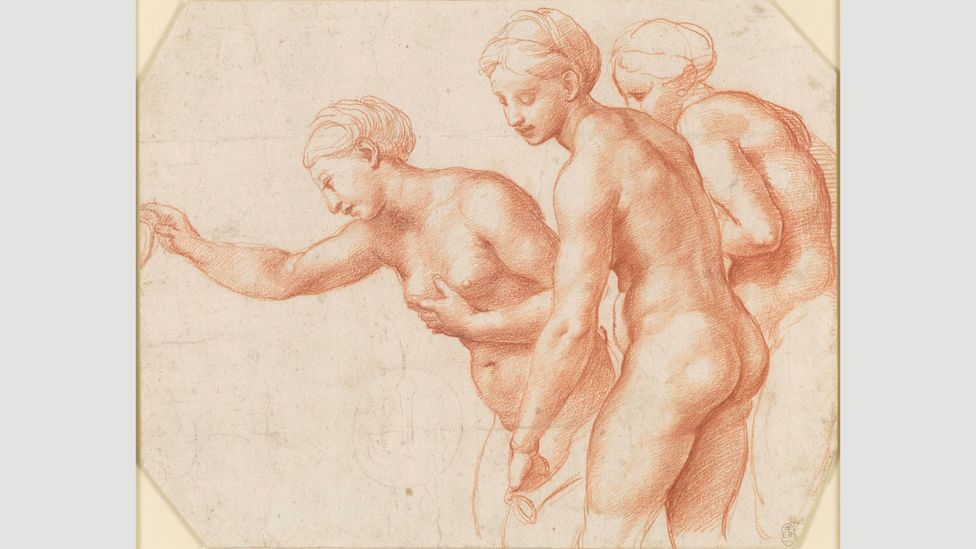

Raphael, The Three Graces, c. 1517-18 (Credit: Royal Collection Trust/ Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth Two 2019)

Drawing on humanist culture and readily available examples of classical statuary, artists began to produce idealised images modelled on the antiquarian. Ghiberti'south panel for the Baptistery doors of Florence cathedral (c 1401-3), which many scholars see as the inception of the Renaissance nude, shows a heroically posed Isaac, the rippling muscles of his chest exquisitely divers in bronze.

As well in Florence, Donatello created an unashamedly sensual sculpture of David (1430-40), his lithe torso and languid pose designed for a civilisation which readily accustomed that "men will detect the torso of a beautiful young man erotic", explains Burke. Indeed, despite existence illegal, aforementioned-sex activity relations appear to have been very much the norm. "More one-half of all Florentine men were indicted for having sexual practice with other men in the 15th Century," says Burke.

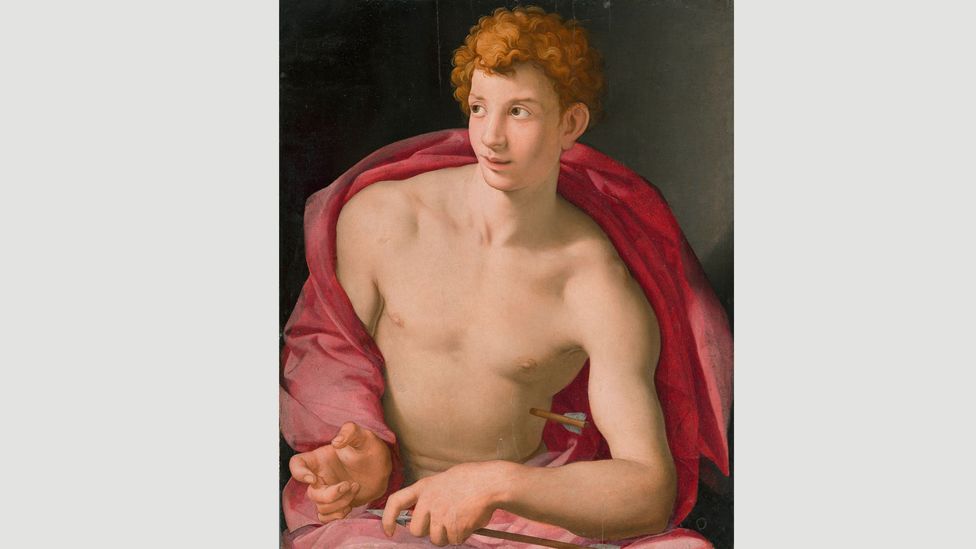

Saint Sebastian was a favourite subject – simply it was not only men who were inflamed by his form. An case by Fra Bartolommeo in the Church building of Saint Marco in Florence "had to be moved because they thought the female congregation were looking at it too eagerly and having evil thoughts about information technology", says Burke.

Agnolo Bronzino, Saint Sebastian, c. 1533 (Credit: Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid)

Despite the unfortunate outcome, there can exist no doubting Fra Bartolommeo's sincere intentions. The same cannot be said for the early 15th-Century illuminated Books of Hours, created for the Knuckles of Berry by the Limbourg brothers. Ostensibly for private devotion, they included images of figures such as Saint Catherine with a pinched-in waist, high-gear up breasts and fragile stake flesh, which bordered on the erotic.

Works such as this fix the stage for the ongoing fusion of the spiritual with the sensual in religious art in French republic. Jean Fouquet's arrival at the court of Charles Seven only heightened this propensity. His portrayal of the king's mistress, Agnès Sorel, as the Virgin Mary (1452-55), her perfectly circular left chest bared to a distinctly uninterested Christ child, was one of the well-nigh bizarre examples.

Madonna surrounded past Seraphim and Cherubim, past Jean Fouquet, 1452 (Credit: Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, Belgium)

These developments did non get unnoticed by the Church and, after the Reformation of 1517, religious imagery was banned from places of worship. Artists in Protestant nations responded by turning to secular and mythological themes of nudity, with Lucas Cranach the Elder producing some 76 depictions of Venus. Information technology gave artists the "selection to explore these themes exterior of the religious sphere which allowed for a huge corporeality of liberty", says the Royal Academy's Assistant Curator, Lucy Chiswell.

The portrayal of nude adult female every bit witches also became popular. In highlighting their supposed sexual ability over men and the need for this to be controlled, it fed into the growing witch craze that saw thousands of women executed. "Information technology's non making the nude grotesque in any mode, but information technology's associating them with these demonic, very potent controlled figures," says Chiswell.

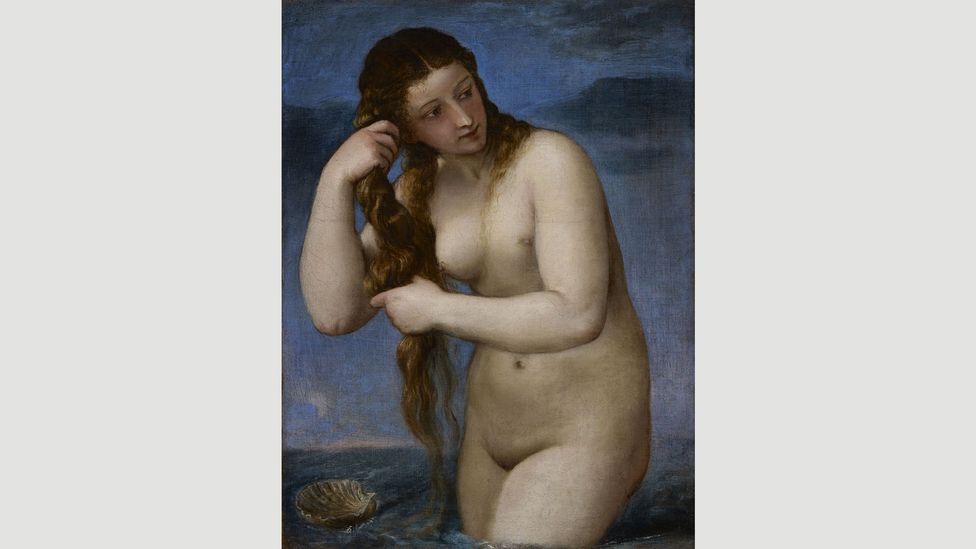

Titian, Venus Rising from the Sea, c. 1520 (Credit: National Galleries of Scotland)

Italia, as well, was increasingly adapting classical themes spurred past the expanding interest in humanist literature and poetry. The Venetian artists Giorgione and Titian produced gloriously voluptuous nudes. But despite their axiomatic eroticism, these paintings were often based on descriptions of classical nudes, allowing their owners to claim their interest was intellectual rather than sexual.

In whatever case, as Shush points out, "one of the testaments of the skill of the artist is to produce a bodily reaction in the viewer – so if you felt erotically aroused by, say, Titian's Venus of Urbino that was a testament to the skill of Titian."

Having purely classical nudes was one thing but the influence of the antique in Catholic religious art was becoming increasingly contentious. Michelangelo, along with the Christian humanists and clerics within his circumvolve, believed a beautiful torso to be the keepsake of human virtue and perfection. But his attempts to reinvigorate Christian art by embracing ancient infidel models in his depictions of Biblical figures for the Sistine Chapel, particularly in The Last Judgement (1536-41), proved too much for the Church. After his death, the genitalia of the figures were covered in drapery.

Afterwards Michelangelo'due south death, the figures he painted in the Sistine Chapel were covered in drapery (Credit: Alamy)

But despite the Church's prudery, Michelangelo's genius was instrumental in the nude coming to exist seen every bit the highest form of artistic expression. After the Sistine Chapel, "everyone wanted their artists to paint nudes", says Burke.

Over time, the nude may have get predominantly female: but for two centuries, the beauty of both sexes was historic by some of the greatest artists who take e'er lived.

The Renaissance Nude is at the Royal Academy in London from three March to ii June 2019.

If yous would similar to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Civilisation, head over to our Facebook folio or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If You lot Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190214-is-the-renaissance-nude-religious-or-erotic

0 Response to "Can I Look at Reniassance Art Not as Pornographic"

Postar um comentário